55+ Chiasmus in Literature Examples

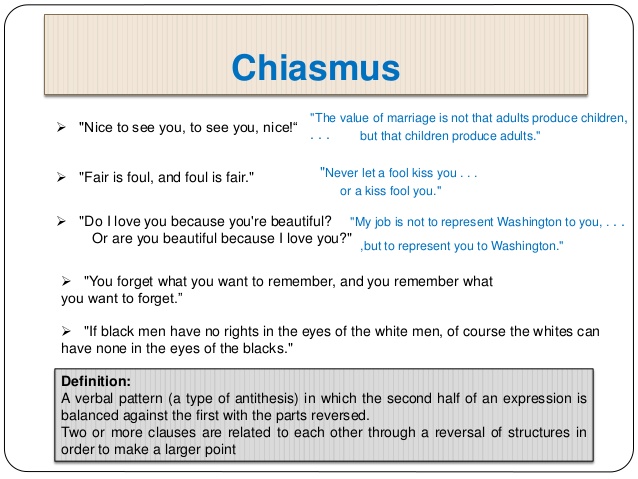

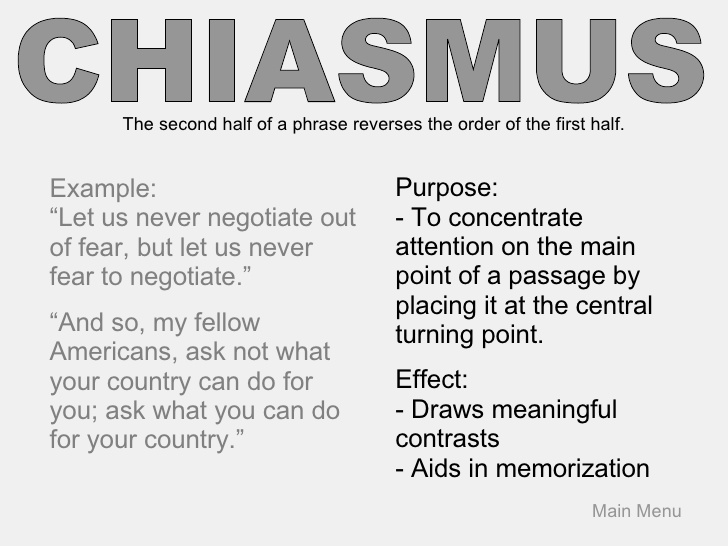

Chiasmus is a rhetorical device used in literature and English writing to create a memorable and impactful effect by reversing the order of words or phrases in parallel clauses. This technique involves placing elements in a mirrored structure, which emphasizes the contrast or creates a balanced, symmetrical pattern. Writers often use chiasmus to highlight key ideas or themes, making their messages more engaging and thought-provoking. By understanding and recognizing chiasmus, readers can appreciate the skillful use of language that enhances the depth and meaning of literary works.

What is Chiasmus in Literature?

Types of Chiasmus in Literature

1. Simple Chiasmus

In simple chiasmus, the order of words in one clause is reversed in the next clause. This creates a mirror-like effect.

2. Antimetabole

This form of chiasmus involves the repetition of words in reverse order. It often highlights a contrast or emphasizes a point.

3. Synchysis

Synchysis involves interweaving words in an ABAB pattern, creating a crisscross arrangement. It often emphasizes the interconnectedness of the ideas.

4. Climactic Chiasmus

This type builds up to a climax, often ending with a strong, impactful statement. The structure draws attention to the final point.

5. Balanced Chiasmus

Balanced chiasmus involves two parallel structures that balance each other in content and form. It creates a sense of harmony and symmetry.

6. Inverted Chiasmus

In this form, the second part of the sentence inverts the order of the first part, but not necessarily word-for-word. It emphasizes the reversal of the idea.

7. Complex Chiasmus

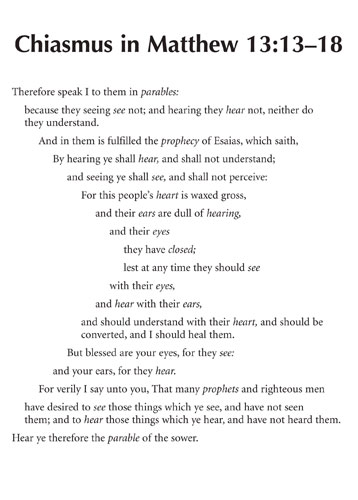

Complex chiasmus involves multiple clauses or phrases that are interwoven and reversed. It can create a more intricate and layered meaning.

8. Narrative Chiasmus

In narrative chiasmus, the overall structure of a story or a large section of text is mirrored. This can highlight central themes or turning points.

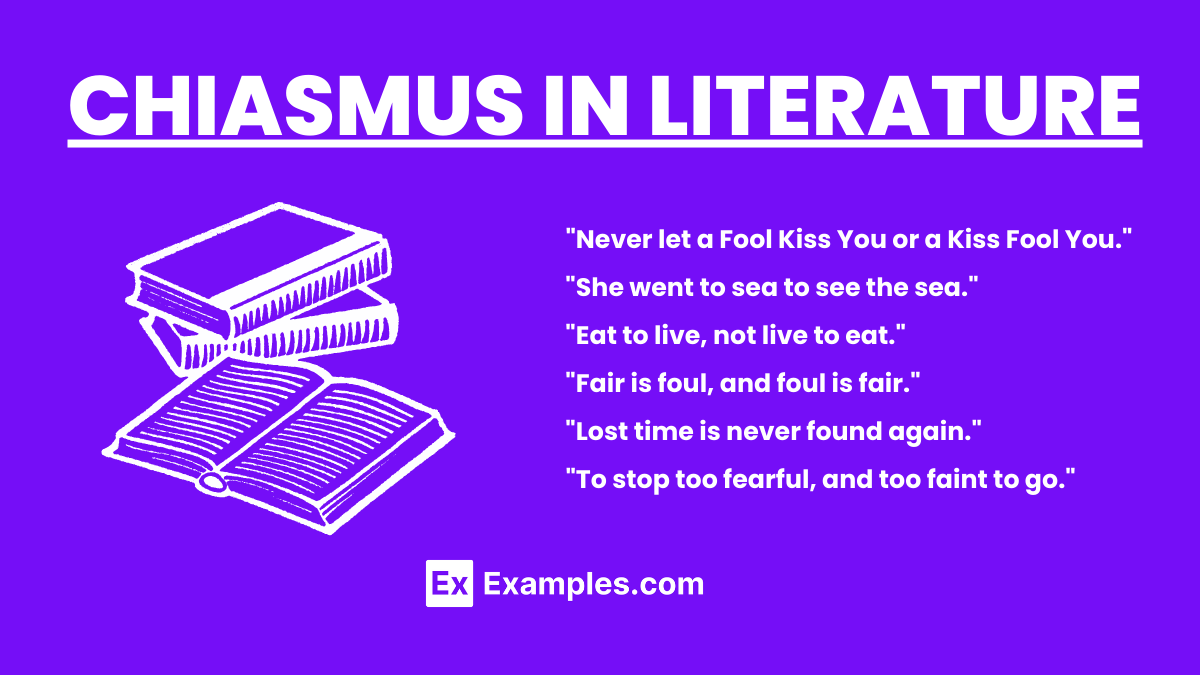

Examples of Chiasmus in Literature

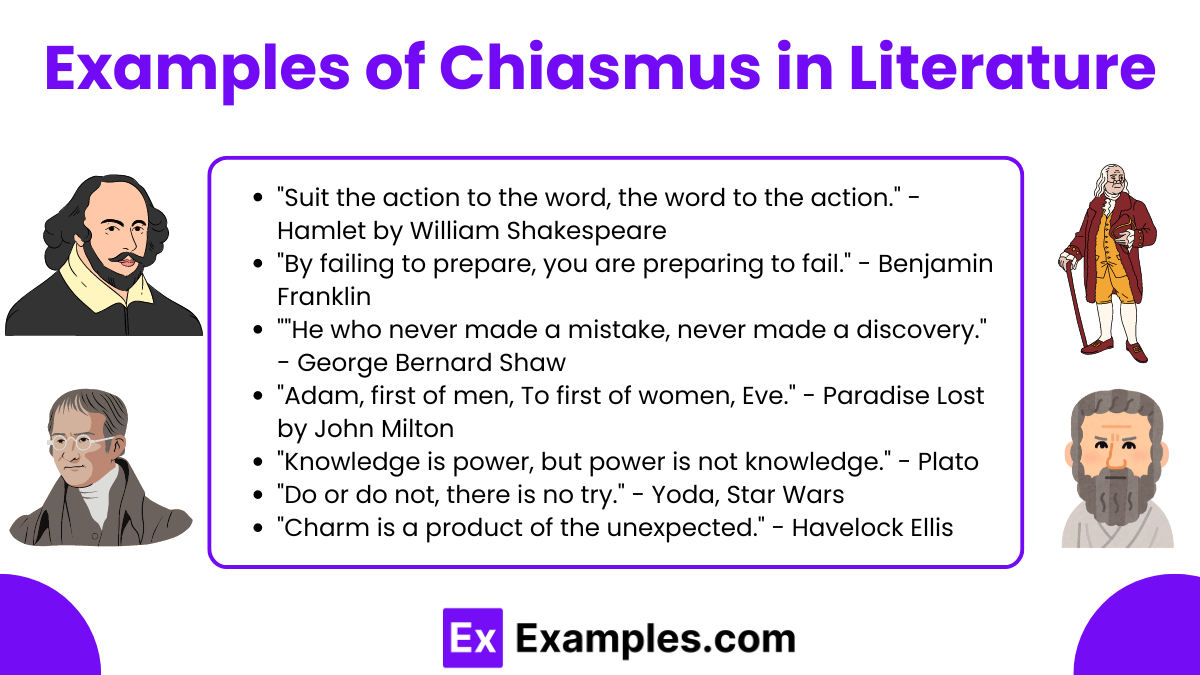

- “Suit the action to the word, the word to the action.” – Hamlet by William Shakespeare

- “Ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country.” – John F. Kennedy

- “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.” – A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens

- “By failing to prepare, you are preparing to fail.” – Benjamin Franklin

- “What lies behind us and what lies before us are tiny matters compared to what lies within us.” – Ralph Waldo Emerson

- “Bad men live that they may eat and drink, whereas good men eat and drink that they may live.” – Socrates

- “He who never made a mistake, never made a discovery.” – George Bernard Shaw

- “Adam, first of men, To first of women, Eve.” – Paradise Lost by John Milton

- “You see things; you say, ‘Why?’ But I dream things that never were; and I say, ‘Why not?'” – Oscar Wilde

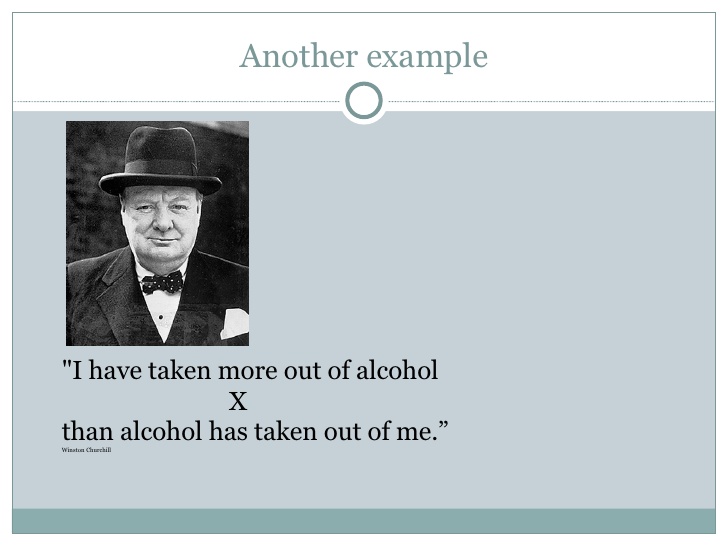

- “We shape our buildings, and afterwards our buildings shape us.” – Winston Churchill

- “Flowers are lovely, love is flower-like.” – Samuel Taylor Coleridge

- “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” – Martin Luther King Jr.

- “Knowledge is power, but power is not knowledge.” – Plato

- “Do or do not, there is no try.” – Yoda, Star Wars

- “Happiness was but the occasional episode in a general drama of pain.” – The Mayor of Casterbridge by Thomas Hardy

- “The poets have been mysteriously silent on the subject of cheese.” – G.K. Chesterton

- “Charm is a woman’s strength, strength is a man’s charm.” – Alexander Pope

- “The only way out is through.” – Robert Frost

- “The end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time.” – T.S. Eliot

- “Charm is a product of the unexpected.” – Havelock Ellis

Examples of Chiasmus in Literature

Chiasmus is not as popular a figure of speech as your superstars simile and metaphor because it tends to create a language that feels too formal or even stilted. Even so, it does appear on your occasional prose and poetry to produce a lyrical and balanced effect. In fact, Chiasmus was very important in some ancient texts since it is entrusted with the responsibility of striking balance in a work of literature.

Othello by William Shakespeare

“But O, what damned minutes tell he o’er

Who dotes, yet doubts; suspects, yet strongly loves.”

Essay on Man by Alexander Pope

“His time a moment, and a point his space.”

Do I Love You Because You’re Beautiful? by Oscar Hammerstein

“Do I love you because you’re beautiful?

Or are you beautiful because I love you?”

Paradise Lost by John Milton

“. . .in his face

Divine compassion visibly appeared,

Love without end, and without measure Grace. . .”

Quote by Judith Viorst

“Lust is what makes you keep wanting to do it. Even when you have no desire to be with each other. Love is what makes you keep wanting to be with each other. Even when you have no desire to do it.”

Quote by John Marshall

“In the blue grass region,

A paradox was born:

The corn was full of kernels

And the colonels full of corn.”

Quote by Alfred P. Solan

“Some have an idea that the reason we in this country discard things so readily is because we have so much. The facts are exactly opposite—the reason we have so much is simply because we discard things so readily.”

Quote by Voltaire

“The instinct of a man is

to pursue everything that flies from him, and

to fly from all that pursues him.”

Quote by Thomas Szaz

“When religion was strong and science weak, men

mistook magic for medicine;

Now, when science is strong and religion weak, men

mistake medicine for magic.”

Quote by Peter de Vries

“The value of marriage is not that adults produce children, but that children produce adults.”

Quote by Alfred North Whitehead

“The art of progress is to preserve order amid change, and to preserve change amid order.”

Quote by Jacquelyn Small

“Don’t sweat the petty things, and don’t pet the sweaty things.”

Quote by Judy Joice

“This isn’t a bar for writers with a drinking problem; it’s for drinkers with a writing problem.”

Quote by Jim Calhoun

“They don’t care about how much you know until they know how much you care.”

Hamlet by William Shakespeare

“Suit the action to the word, the word to the action.”

“For ’tis a question let us yet to prove, whether love lead to fortune, or else fortune love.”

MacBeth by William Shakespeare

“Foul is fair and fair is foul.”

John F. Kennedy in His Inaugural Address

“Let us never negotiate out of fear, but let us never fear to negotiate.”

Song of Myself by Walt Whitman

“The city sleeps and the country sleeps,

The living sleep for their time, the dead sleep for their time,

The old husband sleeps by his wife and the young husband sleeps by his wife;

And these tend inward to me, and I tend outward to them.”

He Lit a Fire with Icicles by Kay Ryan

“This was the work

of St. Sebolt, one

of his miracles:

He lit a fire with

icicles. He srruck

them like a steel

to flint, did St.

Sebolt . . .”

Chiasmus in Literature Examples & Templates

Chiasmus Example

Chiasmus Example Quote

Understanding the Meaning of Chiasmus

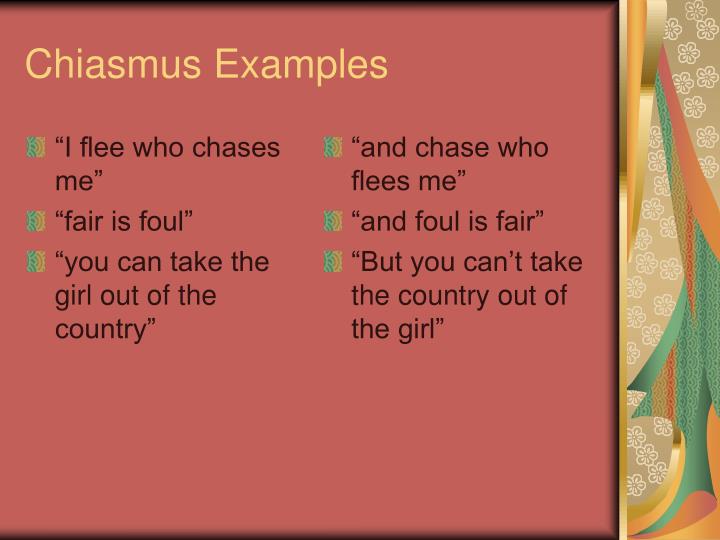

Chiasmus Examples

Chiasmus Quote Example

Chiasmus Examples and Definition

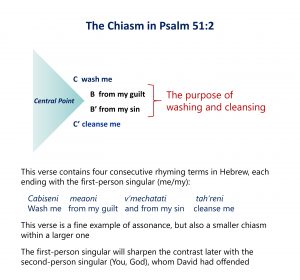

Identifying the Chiasmus in Psalm 51:2

Chiasmus in a Speech

Chiasmus Examples and Purpose

Chiasmus in Bible Verses

Chiasmus Example by John Kennedy

Chiasmus Example from Literature

Chiasmus Meaning and Example

Examples of Chiasmus from Greek Sages

The use of chiasmus as a rhetorical device date back to the ancient Greek and Roman civilizations. Its traces have been found in the ancient texts of Sanskrit and also in ancient Chinese writing. However, the Greeks, unsurprisingly, have developed an unmatched inclination to this specific literary device. They’ve made it a point to make it an essential part of their oration. Here are a few exemplary examples.

Example #1: Aeschylus, 5th Century BC

“It is not the oath that makes us believe the man, but the man the oath.”

Example #2: Bias, 6th Century BC

“Love as if you would one day hate, and hate as if you would one day love.”

Example #3: Socrates, 5th Century BC

“Bad men live that they may eat and drink, whereas good men eat and drink that they may live.”

Chiasmus in Literature Examples for Middle School

- “Bad men live that they may eat and drink, whereas good men eat and drink that they may live.” – Socrates

Highlighting the contrast between living for pleasure versus living for purpose. - “He who fails to plan, plans to fail.” – Unknown

A simple, yet profound statement on the importance of planning ahead. - “When the going gets tough, the tough get going.” – Joseph Kennedy

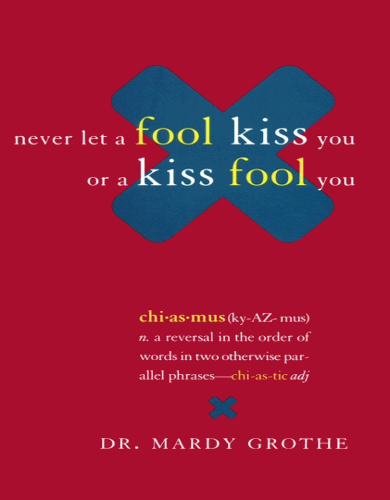

Emphasizing resilience and action in the face of adversity. - “Never let a Fool Kiss You or a Kiss Fool You.” – Mardy Grothe

Playing with the words “kiss” and “fool” to caution against deception in romance. - “You can take the boy out of the country, but you can’t take the country out of the boy.” – Unknown

Reflecting on how one’s origins remain a part of their identity, regardless of where they go.

Chiasmus in Literature Examples for Students

- “Love as if you would one day hate, and hate as if you would one day love.” – Bias of Priene

This encourages a balance of emotions, suggesting that feelings can change over time. - “By failing to prepare, you are preparing to fail.” – Benjamin Franklin

Stresses the importance of preparation for success. - “Ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country.” – John F. Kennedy

A call to service and personal contribution to the greater good. - “It’s not the size of the dog in the fight, it’s the size of the fight in the dog.” – Mark Twain

Emphasizes courage and perseverance over physical attributes. - “To stop too fearful, and too faint to go.” – Oliver Goldsmith

Captures the dilemma of being caught between fear and ambition.

Chiasmus in Literature Examples for High School

- “What is better than wisdom? Woman. And what is better than a good woman? Nothing.” – Geoffrey Chaucer

A playful yet profound reflection on the value of women and wisdom. - “Not all readers are leaders, but all leaders are readers.” – Harry S. Truman

Highlights the importance of reading for leadership. - “In the end, it’s not the years in your life that count. It’s the life in your years.” – Abraham Lincoln

Encourages making the most out of life, not just living a long time. - “The art of love is largely the art of persistence.” – Albert Ellis

Suggests that love requires continuous effort and endurance. - “You have to be odd to be number one.” – Dr. Seuss

Celebrates uniqueness and the importance of standing out to be the best.

Chiasmus in Literature Examples for General Readers

- “Pleasure’s a sin, and sometimes sin’s a pleasure.” – Lord Byron

Reflects on the complex relationship between morality and enjoyment. - “It’s not how much we give but how much love we put into giving.” – Mother Teresa

Highlights the importance of intent over the magnitude of one’s actions. - “Many are called, but few are chosen.” – Matthew 22:14

Suggests that while opportunities may be presented to many, only a select few will make the most of them. - “Let us never negotiate out of fear, but let us never fear to negotiate.” – John F. Kennedy

Advocates for the strength and courage in diplomacy. - “Money is not the root of all evil; the lack of money is the root of all evil.” – Mark Twain

A twist on a common saying, challenging the conventional wisdom about money and morality.

How to Use Chiasmus in Literature

Chiasmus is a powerful rhetorical device that enhances writing by creating a memorable and impactful structure

Understand the Structure

Chiasmus reverses the order of words or phrases in parallel structures.

Ensure Balance and Clarity

Balance the length and structure of the clauses and maintain clear meaning.

Choose Key Moments

Incorporate chiasmus at pivotal points, such as key statements, dialogue, or narrative climaxes.

Identify the Purpose

Balance the length and structure of the clauses and maintain clear meaning.

Revise and Integrate

Revise for impact and ensure the chiasmus fits naturally into your writing

Why is Chiasmus used?

Chiasmus is used to emphasize points, create balance, add dramatic effect, and make language more memorable and engaging.

What is Chiasmus in English Language?

Chiasmus is a rhetorical device where the order of words or phrases is reversed in parallel clauses, creating a mirror-like structure for emphasis and balance.

Does Shakespeare Use Chiasmus?

Yes, Shakespeare frequently uses chiasmus in his works to add dramatic effect and emphasize key themes. An example is “Fair is foul, and foul is fair” from Macbeth.

What is an Example of a Chiasmus Quizlet?

An example of chiasmus is “When the going gets tough, the tough get going.” This illustrates the reversal of word order for emphasis.

Is Chiasmus ABBA?

Yes, chiasmus often follows the ABBA structure, where the elements of the first part are reversed in the second part, creating a symmetrical arrangement.

How does Chiasmus differ from Antimetabole?

Antimetabole is a type of chiasmus that repeats words in reverse order, while chiasmus can involve reversing structures without repeating words.

When should I use Chiasmus?

Use chiasmus at key moments to emphasize important ideas, in character dialogue for depth, or at narrative climaxes for impact.

What are the benefits of using Chiasmus?

Chiasmus enhances the rhythm, balance, and memorability of language, making it a powerful tool in literature and speeches.

Can Chiasmus be confusing?

If overused or poorly balanced, chiasmus can confuse readers. Ensure clarity and natural integration into your writing.

Is Chiasmus common in literature?

Yes, many famous authors and speakers use chiasmus for its rhetorical power and aesthetic appeal.